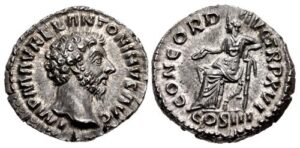

Few things are more exciting than adding special pieces to a collection. Whether you collect artifacts, ancient coins, fossils, minerals, crystals or other antiquities from around the world, Ancient Artifacts & Treasures, Inc. has the inventory selection for you.

The Sacred Art of Eastern Orthodox Icons: A Window to the Divine

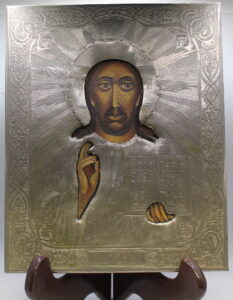

Eastern Orthodox icons are more than just religious paintings; they are windows to the divine, a sacred tradition that has shaped the spiritual life of Orthodox Christians for centuries. Rooted in theology and crafted with meticulous devotion, these icons serve as tools for prayer, teaching, and connection with the divine.

The Theology of Icons

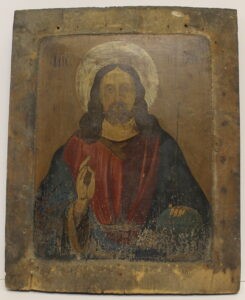

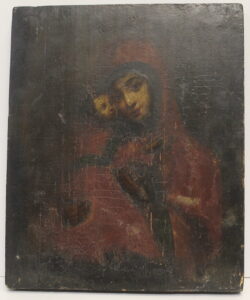

In Orthodox Christianity, icons are not mere representations but are seen as a form of visual theology. They depict Christ, the Virgin Mary, saints, and biblical events in a way that transcends mere artistry.

Icons are believed to convey the presence of the sacred figures they portray, making them objects of veneration rather than worship. This distinction was firmly established in the 7th Ecumenical Council of 787 AD, which affirmed the theological legitimacy of icon veneration.

The Iconographic Tradition

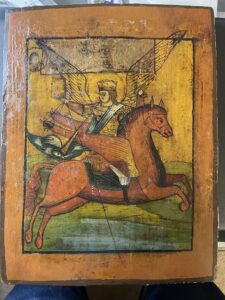

Unlike Western religious art, Orthodox iconography follows strict stylistic conventions. The figures are often elongated, with solemn expressions and large, expressive eyes that symbolize spiritual insight. The backgrounds are typically gold, representing the divine light of heaven. The technique of painting, known as “writing” an icon, follows specific canonical rules to maintain theological accuracy and consistency.

One key feature of Orthodox icons is their symbolic nature. Colors hold deep meaning—gold symbolizes divine presence, blue represents the heavens, red signifies divine life, and white is the color of purity and holiness. Even the way figures are posed conveys theological truths, such as Christ’s right hand raised in blessing or the Virgin Mary pointing toward Him as the source of salvation.

The Role of Icons in Worship

Icons are an integral part of Orthodox worship and private devotion. They are displayed in churches on iconostases—icon screens that separate the sanctuary from the nave—and are also venerated in homes. Believers often light candles before icons, kiss them, and pray in their presence, seeing them as conduits to the divine.

During feast days and liturgical services, special hymns and prayers accompany the veneration of icons. The Orthodox Church celebrates the first Sunday of Great Lent as the “Sunday of Orthodoxy,” commemorating the victory of icon veneration over iconoclasm.

Iconography as a Living Tradition

Despite its deep historical roots, Orthodox iconography remains a living tradition. Contemporary iconographers continue to create new icons following the ancient techniques of egg tempera, gold leaf application, and wooden panel preparation. These artisans often undergo years of spiritual and artistic training, ensuring that each icon remains faithful to the tradition.

Conclusion

Eastern Orthodox icons are more than religious artifacts; they are sacred windows that invite believers into a deeper communion with the divine. Through their rich symbolism, theological depth, and role in worship, icons continue to be a vital part of Orthodox spirituality, linking the faithful across generations in a shared vision of the heavenly realm.