Few things are more exciting than adding special pieces to a collection. Whether you collect artifacts, ancient coins, fossils, minerals, crystals or other antiquities from around the world, Ancient Artifacts & Treasures, Inc. has the inventory selection for you.

If you have ever paddled a canoe, napped in a hammock, savored a barbecue, smoked tobacco or tracked a hurricane across Cuba, you have paid tribute to the Taíno, the Indians who invented those words, and many more, long before they welcomed Christopher Columbus to the New World in 1492.

Their world, which had its origins among the Arawak tribes of the Orinoco Delta, gradually spread from Venezuela across the Antilles in waves of voyaging and settlement begun around 400 B.C. Mingling with people already established in the Caribbean, they developed self-sufficient communities on the island of Hispaniola, in what is now Haiti and the Dominican Republic; in Jamaica and eastern Cuba; in Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands and the Bahamas. There are some experts who feel the natives in the Florida Everglades were also Taino related. They cultivated yuca, sweet potatoes, maize, beans and other crops as their culture flourished, reaching its peak by the time of European contact.

Greater Antilles

Greater Antilles

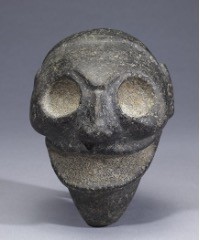

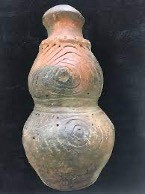

Some scholars estimate the Taíno population may have reached more than three million on Hispaniola by the end of the 15th century, with smaller settlements elsewhere in the Caribbean. Whatever the number, the Taíno towns described by Spanish chroniclers were densely settled, well organized and widely dispersed. The Indians were inventive people who learned to strain cyanide from life-giving yuca, developed pepper gas for warfare, devised an extensive pharmacopeia from nature, built oceangoing canoes large enough for more than 100 paddlers and played games with a ball made of rubber, which fascinated Europeans seeing the material for the first time. Although the Taíno never developed a written language, they made exquisite pottery, wove intricate belts from dyed cotton and carved enigmatic images from wood, stone, shell and bone.

Taino Zemi – Puerto Rico

The Taíno impressed Columbus with their generosity, which may have contributed to their undoing. “They will give all that they do possess for anything that is given to them, exchanging things even for bits of broken crockery,” he noted upon meeting them in the Bahamas in 1492. “They were very well built, with very handsome bodies and very good faces….They do not carry arms or know them….They should be good servants.”

In short order, Columbus established the first American colony at La Isabela, on the north coast of Hispaniola, in 1494. After a brief period of coexistence, relations between the newcomers and natives deteriorated. Spaniards removed men from villages to work in gold mines and colonial plantations. This kept the Taíno from planting the crops that had fed them for centuries. They began to starve; many thousands fell prey to smallpox, measles and other European diseases for which they had no immunity; some committed suicide to avoid subjugation; hundreds fell in fighting with the Spaniards, while untold numbers fled to remote regions beyond colonial control. In time, many Taíno women married conquistadors, combining the genes of the New World and Old World to create a new mestizo population, which took on Creole characteristics with the arrival of African slaves in the 16th century. By 1514, barely two decades after first contact, an official survey showed that 40 percent of Spanish men had taken Indian wives. The unofficial number is undoubtedly higher.

Possibly as many as three million souls—some 85 percent of the Taíno population—had vanished by the early 1500s, according to a controversial extrapolation from Spanish records. As the Indian population faded, so did Taíno as a living language. The Indians’ reliance on beneficent icons known as cemís gave way to Christianity, as did their hallucinogen-induced cohoba ceremonies, which were thought to put shamans in touch with the spirit world. Their regional chieftaincies, each headed by a leader known as a cacique, crumbled away. Their well-maintained ball courts reverted to bush.

Given the dramatic collapse of the indigenous society, and the emergence of a population blending Spanish, Indian and African attributes, one might be tempted to declare the Taíno extinct. Yet five centuries after the Indians’ fateful meeting with Columbus, elements of their culture endure—in the genetic heritage of modern Antilleans, in the persistence of Taíno words and in isolated communities where people carry on traditional methods of architecture, farming, fishing and healing.

More than 1,000 years before the Spaniards arrived, local shamans and other pilgrims visited such caves to glimpse the future, to pray for rain and to draw surreal images on the walls with charcoal: mating dogs, giant birds swooping down on human prey, a bird-headed man copulating with a human, and a pantheon of naturalistically rendered owls, turtles, frogs, fish and other creatures important to the Taíno, who associated particular animals with specific powers of fecundity, healing, magic and death.

The cohoba ritual was first described by Friar Ramón Pané, a Hieronymite brother who, on the orders of Columbus himself, lived among the Taíno and chronicled their rich belief system. Pané’s writings—the most direct source we have on ancient Taíno culture—was the basis for Peter Martyr’s 1516 account of cohoba rites: “The intoxicating herb,” Martyr wrote, “is so strong that those who take it lose consciousness; when the stupefying action begins to wane, the arms and legs become loose and the head droops.” Under its influence, users “suddenly begin to rave, and at once they say . . . that the house is moving, turning things upside down, and that men are walking backwards.” Such visions guided leaders in planning war, judging tribal disputes, predicting the agricultural yield and other matters of importance. And the drug seems to have influenced the otherworldly art in Pomier and other caves.

Cahoba Vessel – Puerto Rico

At Sabana de los Javieles, a village known as a pocket of Taíno settlement since the 1530s, when Enrique, one of the last Taíno caciques of the colonial period, made peace with Spain and led some 600 followers to northeastern Hispaniola. They stayed, married Spaniards and Africans, and left descendants who still retain indigenous traits. In the 1950s, researchers found high percentages of the blood types that are predominant in Indians in blood samples they took here. And a recent nationwide genetic study established that 15 percent to 18 percent of Dominicans had Amerindian markers in their mitochondrial DNA, testifying to the continued presence of Taíno genes. A study published in the Journal Nature, shows that, on average, about 14 percent of people’s ancestry in Puerto Rico can be traced back to the Taino.

Relegated to a footnote of history for 500 years, the Taíno came roaring back as front-page news in 2003, when Juan C. Martínez Cruzado, a biologist at the University of Puerto Rico, announced the results of an island-wide genetic study. Taking samples from 800 randomly selected subjects, Martínez reported that 61.1 percent of those surveyed had mitochondrial DNA of indigenous origin, indicating a persistence in the maternal line that surprised him and his fellow scientists. The same study revealed African markers in 26.4 percent of the population and 12.5 percent for those of European descent.

Dr. Aviles, now a physician in Goldsboro, N.C. who studied genetics in graduate school, and his colleagues have uploaded the ancient Caribbean genomes to a genealogical database called GEDMatch. With the help of genealogists, people can compare their own DNA to the ancient genomes. They can see the matching stretches of genetic material that reveal their relatedness.

We are finding that the Taino are still living among us.

Comments are closed.